As health risks increase, so does the demand for climate adaptation.

By Florence Fahringer

Original Air Date: November 15, 2024

Host: Climate change and human health are closely linked — think along the lines of heat stroke, mosquito bites, and your and my sanity after this storm season. Florence Fahringer was at a conference in Sarasota yesterday. Here is her report.

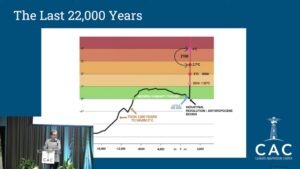

Florence Fahringer: What impact does a changing climate have on human health? That’s the question the Climate Adaptation Center set out to answer this week, hosting medical professionals at a two-day conference on the USF Sarasota-Manatee campus. There were five sessions in all, dividing the topic into five parts: heat, disease, air quality, mental health, and migration. To begin, Bob Bunting, climate scientist and CEO of the Climate Adaptation Center, talks heat.

Bob Bunting: Believe it or not, heat is the deadliest weather phenomenon in the United States. It’s not floods; It’s not hurricanes; It’s hard to believe, but it’s heat. We know every minute when a hurricane is coming. There are planes flying in, reports coming out, all the  news media is covering it. But yet when we have a heat wave and thousands of people die, we really don’t know until later that that really happened.

news media is covering it. But yet when we have a heat wave and thousands of people die, we really don’t know until later that that really happened.

I don’t lose sleep over much. I’m a climate scientist. I’ve been through this for a long time. I’ve thought about the worst case scenarios, okay, so I sleep pretty good. But this is one that keeps me up at night, when there’s a hurricane during the summer coming on shore in Sarasota, where we know we’re going to lose power for a week or two, and could be followed by 95° days every day, with no air conditioning, with no way to leave, 24 million people. We are on the edge of having a catastrophe from heat, and people don’t realize it.

Bob Bunting

FF: Doctor Ankush Bansal, physician and associate professor at Florida International University, talked about what can be done to reduce the medical risks of the increasingly oppressive heat.

Ankush Bansal: So the first is heat health warning systems. So a heat early warning system uses weather and climate forecasts to help people prepare for and reduce the health effects of extreme heat. But the heat early warning system then leads to a heat health action plan, that includes the warning systems for both policies and strategies to reduce the health effects of extreme heat, at any governmental level. So it’s local, that’s your HOA, that’s the county, the state, the city, as well as nationally. Miami Dade, for example, has an extreme heat action plan, and that was developed by the Chief Heat Officer of Miami Dade — which, by the way, was the first Chief Heat Officer of any city in the entire world.

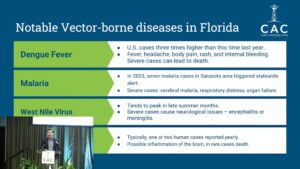

FF: Ric Kearbey, former TV meteorologist and current senior scientist at the Climate Adaptation Center, introduced the risks of tropical diseases creeping into subtropical Florida.

Ric Kearbey: Warmer weather makes vector insects more dangerous. So, we’re talking things like mosquitoes and ticks. One thing it  does is it extends their habitats. So, vectors are now surviving in places where it was previously too cold. A warming climate also creates longer transmission seasons. So, milder winters means that the mosquito season can lengthen. And also inside those vectors, the pathogens are more active and more effective as it warms. So, it’s kind of a double threat there.

does is it extends their habitats. So, vectors are now surviving in places where it was previously too cold. A warming climate also creates longer transmission seasons. So, milder winters means that the mosquito season can lengthen. And also inside those vectors, the pathogens are more active and more effective as it warms. So, it’s kind of a double threat there.

FF: Doctor Kathryn Lago has traveled the world, serving in the Army in a medical capacity. She’s a bit more familiar with the tropical diseases described by Kearbey, and the ways that countries in the tropics tackle such threats.

Kathryn Lago: In Thailand, a huge part of their treatment is public education and patient education, because dengue is a huge  problem in Thailand. So, everywhere you go, they have these pictures of like little … that’s an Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is the vector for dengue. You can tell it’s a black mosquito with little white stripes. So if you’re looking in your yard, that’s … avoid that one. But it kind of tells patients what dengue is like, how to avoid it, and prevention measures, which is something that we really need to work on in the United States.

problem in Thailand. So, everywhere you go, they have these pictures of like little … that’s an Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is the vector for dengue. You can tell it’s a black mosquito with little white stripes. So if you’re looking in your yard, that’s … avoid that one. But it kind of tells patients what dengue is like, how to avoid it, and prevention measures, which is something that we really need to work on in the United States.

FF: Mental health is one of the more underappreciated areas of adversity in the face of climate change. Kearbey highlighted the profound effect climate disaster has on our mental wellbeing.

RK: Nearly 60% of young people are either very or extremely worried, and 45% in this Huffington Post article say they have negative effects on their daily life and functioning. Believe it or not, it’s causing PTSD, and in some cases, suicidal thoughts. People affected by weather disasters you see here, there’s a percentage that do have those suicidal thoughts. And if you look up some studies back in Hurricane Katrina, there was an increase of suicidal thoughts from 2.8% to 6.4%.

FF: Florida is a hotspot for the adverse effects of climate change. It’s also the fastest growing state in the US. Bunting touched on how we may see migration patterns reverse in the sunshine state in the decades to come.

BB: We’ve had a huge migration into Florida since 1990, but by 2050, those arrows may change the other direction. So, a phased retreat really is what’s happening. So, escalating losses is having its impacts, and there’s a wealth shift. People who cannot afford the risk are going to move to other places and people who can afford the risk are going to move in. So in a way, the cycle that we’re going to see is actually going to be more wealth, by people who can afford to take the risk on the barrier islands.

We’re not deserting the barrier islands, but the change of the people who actually decide to live there is going to change. And the services that those people are going to want, will be able to afford to build. At some point, long term, that’ll be the last part of this cycle.

FF: David Altig, executive vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, says it doesn’t look like Florida’s migration reversal is coming anytime soon though.

David Altig: Here’s the challenge. First of all, if I’m here, assume population growth. I mean, it’s going to happen. This is a nice place. It’s got low taxes. This is a place to be. Now, some people will get scared away, and we heard a lot about that. But the last 10 years didn’t scare anybody away. And the last 10 years, as Bob’s chart showed, demonstrated plenty of risk.

Now, some of that maybe can be managed by moving to less risky areas, but I want to point out something. I want to point out that often when people move, say, to higher ground, further away from the water so that you mitigate some of the flooding risk, you’re moving into the places where people of lesser means already live. And they live there because they can’t afford to live closer to where you live. And as you move out, you’re moving them out too. We see it time and time again. This is the huge development problem. The huge development problem is, we displace people, and have no plan to deal with it.

FF: This is Florence Fahringer, reporting for WSLR News.

WSLR News aims to keep the local community informed with our 1/2 hour local news show, quarterly newspaper and social media feeds. The local news broadcast airs on Wednesdays and Fridays at 6pm.