Nitrogen load in river mirrors algae bloom duration on Gulf Coast.

By Johannes Werner

Original Air Date: July 3, 2024

Host: Nobody living along the Suncoast has been able to ignore Red Tide. But many insist it is a naturally occurring phenomenon that has been around for thousands of years. And the link between human activity and the increasing length and intensity of Red Tide has not been exactly at the forefront of interest by the State of Florida, or even public universities and marine research institutions. But now, a scientist in Sarasota and four colleagues are making a dent in the armor of silence around Red Tide and human activity. Our news team talked to Dr. David Tomasko.

Johannes Werner: Tomasko is the executive director of the Sarasota Bay Estuary Program, a partnership of local cities and counties and the Southwest Florida Water Management District. The Estuary Program is not exactly known as a powerhouse of research. That badge of honor belongs to institutions such as Mote Marine or USF’s College of Marine Science in St. Petersburg.

Yet Tomasko’s research on the nitrogen load in five regional rivers and its link to Red Tide could be considered groundbreaking. And it was just published in the peer-reviewed journal Florida Scientist.

Dr. David Tomasko

Dave Tomasko: We were notified by the editor of Florida Scientist that our paper was accepted for publication. It hasn’t come out yet; they only publish four times a year. But we anticipate it, we know that it is accepted, and we know what it contains because we wrote the thing! [laughter] So we’re pretty comfortable that it would get accepted, but it’s a complex topic and we wanted to make sure that when we talk to the public that we don’t just give our opinion, we give conclusions that are based upon the scientific process, which means outside external peer review. And that’s what we have now.

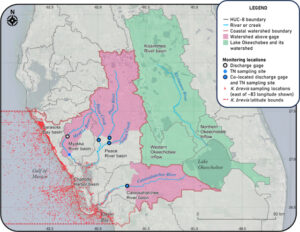

JW: This is not the first published research on the link between human activity and Red Tide. Two local studies elsewhere in Florida preceded Tomasko’s. But the Sarasota researchers’ look at the Caloosahatchee and four other rivers in Southwest Florida is the so far most extensive study. And it clearly established the link between nutrient loads in the Caloosahatchee – the river that links Lake Okeechobee and the Gulf of Mexico – and Red Tide along the Suncoast.

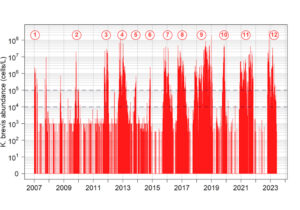

DT: So we’ve got these 11 events, and this is what’s called a retrospective analysis. So after we’ve got these 11 events, we know when it started and when it ended. And what we looked at is, for each of the 11 events, we didn’t look at the nutrient load during the same time period, because if we did that, it would be double counting, and that would be what we call a spurious correlation. So instead, we said for each of those different 11 events, let’s look at the nutrient load 30 days before that event started and then the first 30 days of that event.

The graph shows the duration and intensity of 11 recent Red Tide blooms.

So, each of those 11 events, we compared 60 days of nitrogen load against the duration of the event. It’s called just a regression analysis. And when we did that, we found that we could predict the duration of red tide events 77% of the variability can be accounted for by the nutrient load in the very beginning of that event. So, a big nutrient load, you’re going to have a long lasting event. A small nutrient load, it’s not going to last very long. And the probability that that correlation was due to chance alone is less than one in a thousand. So in other words, the nutrient load that has been delivered before the start and the first month of that red tide event has a strong influence on how long you’re going to have red tide.

And the biggest tide event we had that went from 2017 all the way into 2019 was associated with a huge pulse of nitrogen associated with a passage of Hurricane Irma. And so Irma loaded up the near shore Gulf of Mexico with nutrients. When we got a Red Tide, it was going to be a long lasting Red Tide because it was fueled early on by a lot of nitrogen made available.

JW: What does Tomasko think should be done? For one, revive the decade-and-half old, but unfulfilled commitment by the State of Florida to reduce nitrogen loads in rivers.

DT: We are loading two-to-four times as much nitrogen into our coastal waters as what happened when Florida was occupied by the Calusa and visited by the conquistadors. So we are basically loading up our near shore waters with more nitrogen and we’re making Red Tides larger, longer lasting, and more intense. So what makes sense is, let’s stop loading as much nitrogen.

The biggest factor that drove the Red Tide duration that we found was the Caloosahatchee River, and the nitrogen loads coming out of the Caloosahatchee River equal the nitrogen loads from the entirety of the Peace and Myakka Rivers. It’s that big of a nutrient loading source. So the Caloosahatchee River is the key. Get the nitrogen loads in the Caloosahatchee River under control, and you’re going to be able to have not only good conditions when you don’t have a Red Tide, but when you do have a Red Tide, it should be less intense, smaller, and not as long lasting.

Nitrogen loads in the Caloosahatchee River (pink area, bottom of map) mirrored Red Tide outbreaks (in red) along the Gulf Coast in Southwest Florida.

So really what it comes down to is, we need to reduce the nutrient loads coming out of the Caloosahatchee River. And to do that, we need to reduce the amount of water coming out of the Caloosahatchee River. And that is a big challenge, but at least we know that there’s going to be a benefit that’s going to be commensurate with the challenge. Imagine being able to have less intense Red Tides, shorter Red Tides, smaller Red Tides. That is a possibility if we can fully implement the State of Florida’s 15-year-old plan to reduce nitrogen loads by 23% coming out of the Caloosahatchee River. That was their goal set back in 2009. It’s just not been implemented.

So the problem we have is, it’s not so much that the water in the Caloosahatchee River is that much more laden with nitrogen than any other river. It’s not. It’s elevated and it’s a little bit different. The biggest problem we have is there’s so much water. And what we need to do is … there’s not a wastewater treatment plant that can fix this, there’s not a magic reservoir downstream from the lake that can fix it. The C43 reservoir is a good project. It’s not big enough. What we need to do is, we need to start working up north of the lake. We need to hold more water in place before it gets to the lake. Because we can’t just bring it into the lake and then send it to the south because it’s not clean enough. If you sent that water to the south, you would dump so much phosphorus into the Everglades, you’d turn it into a cattail marsh. We can’t just hold it in the lake, because the lake is like five-to-seven feet lower than it used to be, because we drained the lake and lowered it a hundred years ago. So, the only thing that actually probably has a good probability of success is to work above the lake to stop how quickly we drain water into the lake, and that way we won’t have as much water that needs to be discharged.

JW: The Caloosahatchee link seems to point the finger at agriculture. But what about the link between suburban sprawl in this region and algae blooms? Tomasko believes more people and homes don’t necessarily mean more water pollution.

DT: One of the things that we can really highlight is, more people doesn’t necessarily mean more pollution. It depends on how you handle the wastewater and stormwater. So, for example, Sarasota Bay is cleaner now than it’s been at any time in the last 10, 15 years. Yet we have more people. And what, how is it cleaner? It’s cleaner because we’re doing a better job with stormwater. We’ve retrofitted 5,000 acres of our watershed. We’re doing a much better job with wastewater. And so, Tampa Bay. Tampa Bay’s got some problems, but it’s cleaner now than it was 50 years ago. So is Chesapeake Bay. Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River. I’m originally from Washington D.C. Potomac River is much cleaner than it was in the 70s, even though there’s a lot more people. But more people doesn’t necessarily mean more pollution. It’s what you do with their stormwater runoff. It’s what you do with their wastewater. And one of the things that’s a little bit of a red herring is, we like to think that it’s the new people that are causing the pollution. But the reality is, if you put in a new development right now, you’re gonna have to have regional stormwater treatment. The biggest problem we have in Sarasota Bay after the big rain event we had two weeks ago was not the new development. It’s the old neighborhoods. It’s the areas that were built before the 1980s that actually don’t have any stormwater treatment. It’s the leaky sewer pipes from infrastructure that might be decades old. So new development can be a pressure, for example, on things like wildlife, like panthers and all that. But new development doesn’t necessarily mean more pollution.

JW: Reporting for WSLR News, this has been Johannes Werner.

WSLR News aims to keep the local community informed with our 1/2 hour local news show, quarterly newspaper and social media feeds. The local news broadcast airs on Wednesdays and Fridays at 6pm.