Plaintiffs say Sarasota County violated its own policies.

Johannes Werner

Original Air Date: Jan. 22, 2024

Host: A lot hinged on that court hearing yesterday in Hutchinson and Fitzgerald vs LWR Communities and Sarasota County: On one side, the end of agriculture and rural lifestyles in east Sarasota County. On the other side, up to 5,000 homes the developer of Lakewood Ranch wants to build, and the way Sarasota County amends its comprehensive plan. WSLR News listened to the oral arguments before the Second District Court of Appeals in Tampa.

Johannes Werner: The three-judge panel has yet to rule on the matter. But the questions the judges asked during the 45-minute video hearing—and the answers they got from Richard Grosso, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, and Tara Price, the developer’s lawyer—hinted at where they might be leaning.

First, Grosso laid out the reasons why the plaintiffs appealed an administrative law judge’s ruling in favor of the developer and county. First and foremost, Grosso argued, that’s because that judge misunderstood comprehensive plan changes. The amendment the Sarasota County Commission passed two years ago to accommodate the Lakewood Ranch Southeast project contradicts one of the underlying policies of the comprehensive plan—to protect agricultural land.

Richard Grosso, plaintiffs’ lawyer.

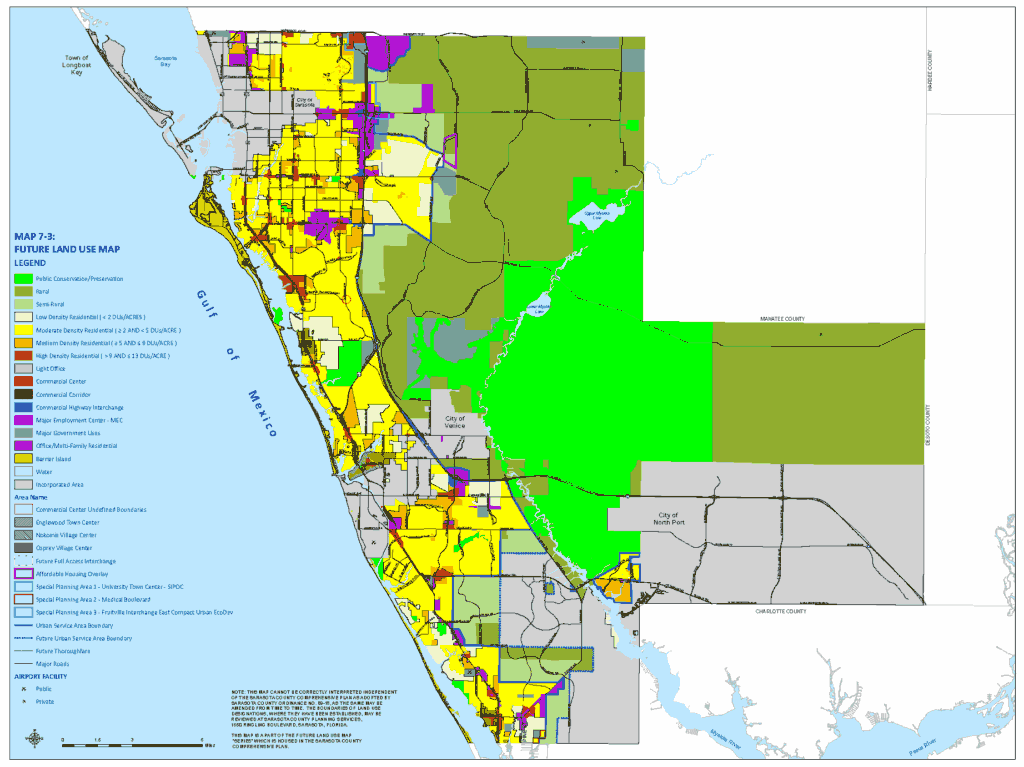

Richard Grosso: There’s a policy, Policy 2.2.1, in the Sarasota County Comprehensive Plan, that says “maintain and protect agriculture.” This plan amendment changes the Comprehensive Plan allowance for a 4,000-acre piece of land. You could only do 1,648 development units on that property before this change happens to the Future Land Use Map. And it’s a subcategory. They didn’t change the entire Future Land Use category. They just said, “We’re giving you a subcategory, and now, in that category, you can do three times the amount of development you could do before.”

JW: One of the three judges, Robert Morris, challenged Grosso, suggesting Hutchinson and Fitzgerald filed their lawsuit too early. They should have waited until specific site plans are filed.

Robert Morris: Is this an argument for another day and another forum and another process?

RG: No. It is not. That’s the fundamental legal error, Judge Morris.

RM: But the policy is still going to be—of the county—unless it’s changed—to preserve agricultural lands. It’s still going to be there, so that argument’s still very much alive there, when it’s really more relevant than it would be at this moment.

Judge Robert J. Morris.

RG: I get your point there, but yet—now you’ve affirmatively changed the plan to say, “despite the ‘maintain and protect agriculture’ language, we’re going to approve a density increase.” The whole idea of planning upfront is that you only plan for the uses that have been deemed appropriate so that after developers down the line, later—a year from now, two years from now—they don’t come in for approvals that—”oh, well, we’re going to deny them now.”

RM: But why then have those subsequent processes if this now becomes a slam dunk?

RG: Yes. Because the subsequent processes are much more about the micro-detail of a specific site plan. Maybe it’s not going to be 5,000 whole units. Maybe—

RM: Well, but this is a macro detail. This is about preserving the agricultural integrity of this land, so I have a hard time following your argument, because it sounds like, once the Comprehensive Plan says it, it’s over. I don’t know why you have the rest of these planning processes.

JW: Chief Judge Daniel Sleet headed in the same direction.

Judge Daniel H. Sleet.

Daniel Sleet: It appears that you’re saying that there’s no way a developer following the law with the County Commission can amend the Comprehensive Plan to redesignate agricultural to rural. Is that what you’re saying?

RG: That’s what the plan says: “maintain and protect.” If the county—

DS: That defeats the purpose. So you’re telling me that it will never change? But, see, your property—your client’s property—is still agricultural.

RG: Yes.

DS: The LTZ is not. It’s rural. Right?

JW: But Grosso held his own.

Future Land Use Map from Sarasota County’s Comprehensive Plan.

RG: This is the decision, the Change of Future Land Use Map: We are going to maintain this land as rural, or we are going to urbanize it. That is the decision that’s made here. It’s a decision that must comply with all of the rules. You have to analyze all the things that are going to happen, including traffic. You have to apply those policies—in this case, maintain or protect agricultural uses. Those are on the table now. If you wait to challenge them later, it’s too late under this statutory scheme. You can’t tell a developer now, “We’re giving you a maximum of 5,000 units on your property,” and then they come in for the actual building permits and development orders later and, “oh, we’re actually not going to give it to you.”

JW: Judge Sleet then challenged Grosso on the notion of policy, such as protecting agriculture. Sleet argued that policy behind comprehensive plans is aspirational and can be changed.

Grosso responded that this is true. But if policy is changed, it should be done as a conscious act, not piecemeal.

RG: I don’t disagree with a word of that, Your Honor. There’s a point I would make about that. The policy decision to make remains always. If the local government wants—it perceives changed circumstances, it perceives it’s running out of land to meet the projected population—for whatever other valid legislative reason, it decides a policy to maintain and protect agricultural land, strictly applied, no longer is appropriate, that’s where the ability to come in and amend that policy comes in. You can’t amend your policy decisions by making future land use changes that flout them. You have to go in and change the policy for the very reasons, Judge Sleet, that you raised.

JW: Throughout this, the lawyer representing Sarasota County remained quiet and let the developer’s lawyer do the arguing.

When questioning the developer’s lawyer, Judge Morris seemed to turn around and made this statement:

RM: But the reality of it is, once the horse is out of the barn and the corral, and it’s in the pasture, it’s really hard to get the horse back, and that’s what this process is about. The horse is coming out of the barn—coming out of the corral—and as much as you heard me talk to your opponent, taking the position you’re taking now, I couldn’t even talk myself into it. Clearly the gate is open, and it’s really hard to close the gate after this process is completed.

JW: Mike Hutchinson and his wife and co-plaintiff Eileen Fitzgerald, who own a home at Bern Creek, a big-lot subdivision in the rural area along Fruitville Road, have invested tens of thousands of dollars—and going—in their lawsuit.

We asked him how he felt after the hearing.

Mike Hutchinson.

Mike Hutchinson: We felt better after. We thought it went a little bit our way. That was good. It’s always a tough fight when you’re appealing against something that was against you in the first place. You have to convince them that—it was sort of interesting. Judge Morris, when he was asking some of the stuff early on, made it sound like he was going to rule against us, and then when the other side went, sounded like he was going to rule for us. It looked like he was just asking tough questions. He did his homework, and he was asking tough questions.

JW: Ahead of yesterday’s hearing, Hutchinson let the developer and county know that they are wasting their—and taxpayers’—money by continuing the process towards development not if but when the courts rule in his favor.

MH: They’re legally allowed to go ahead. They can do whatever they want, because at this point, it’s been approved, but if we win the appeal, they have to put it all back the way it was.

JW: Even though the defendants have argued the plaintiffs have no legal standing, they did not ask the court to dismiss the appeal. The judges will now have to weigh the arguments and rule on the case, which could, according to Grosso, take anywhere from a couple of weeks to a year. Stay tuned.

Reporting for WSLR News, this is Johannes Werner.

WSLR News aims to keep the local community informed with our 1/2 hour local news show, quarterly newspaper and social media feeds. The local news broadcast airs on Wednesdays and Fridays at 6pm.