We hear from the wife of a detainee, from a senior citizen who is leaving the United States, and from a 16-year old activist.

By Ramon Lopez

Original Air Date: January 16, 2026

Host: Last Sunday, WSLR News reporter Ramon Lopez tagged along on a bus trip with a group of Sarasota clerics, worshippers and activists to a protest at the controversial immigration detention camp in the Everglades. Here is the report he filed.

Ramon Lopez: Last Sunday, SURE (Sarasota United for Responsibility and Equity) conducted a solidarity bus trip to Big Cypress Detention Center, commonly known as Alligator Alcatraz. It was the second one held there by the local faith based community organization.

“Love all our neighbors.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

The protest participants made a noon departure from the Unitarian Universalist Church of Sarasota. The bus was only half full due to the short notice, but SURE executive director and lead organizer Michelle Jewell made the best of it and got the ball rolling by asking those aboard the tour bus why they came along.

First up at bat was Michelle Jewell herself.

Michelle Jewell: I am the daughter of a Colombian immigrant, and this hits very close to home. Although I was born in the US, I always identified as Colombian. To see my mother suddenly get scared to walk in our neighborhood is heartbreaking. It’s devastating because she’s a powerhouse. I mean, she’s a tiny little thing, but nothing’s ever broken her spirit except for now. To hear her say that she’s scared to walk in our neighborhood because someone might not like the color of her skin or the accent that she has—because, even though she’s been here for 50 years, she’s always going to have an accent—it’s heartbreaking.

RL: Democrat Manny Lopez, who failed to unseat conservative US Republican Representative Greg Steube in the last election, unloaded. He said:

Manny Lopez: Keep the vigilance, keep it out there, keep the voice, spread it around because it does make a difference. We gained civil rights, we ended the Vietnam War, and we did other things by repetitively pounding the horn and sending the message. We’ve got to keep it up or we will lose our democracy, and it is too valuable to give up without a fight. We are fighting for this with resistance and people like you coming out here for these things. Thank you for being here, everybody.

“Not on our watch; not in our nation; not to our neighbors.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: The voyage involved 16 area clergy and worshippers who stand with undocumented immigrants detained at the Florida-run detention facility in the Everglades. They met up with about 350 other faith leaders and social justice group activists when they arrived at the isolated destination. The other protesters were locals or came by bus from Naples, Fort Myers and other towns in Florida.

The Sarasotans joined the others for the regular Sunday protest and prayer vigil, a peaceful gathering against alleged inhumane treatment and violations of constitutional rights at the ICE lockup. The demonstration is organized and funded by The Workers Circle and the Miccosukee Tribe, which is suing the feds. Their objective: Shut down Alligator Alcatraz.

This, as Florida is awaiting approval from federal officials to open a third detention center in the Florida panhandle following Alligator Alcatraz and Deportation Depot. And the state is looking into a potential fourth facility somewhere in South Florida.

But the prayer and protest was underscored by the January 7 killing of Renee Nicole Good, a 37-year-old US citizen and mother of three fatally shot by an ICE agent in Minneapolis. Her death sparked outrage and more than 1,000 ICE Out For Good protests across the country last weekend. Local rallies were held in Sarasota, Englewood, Venice and Bradenton last Saturday to highlight the human cost of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement actions.

Photo by Ramon Lopez

The nonviolent demonstration was along the two-lane road leading up to the front gate of Alligator Alcatraz, over a mile away. It was led by Noelle Damico, Director of Social Justice for The Workers Circle.

Noelle Damico: Gabriel Garcia-Aviles.

Crowd: Presente.

ND: Kai Yin Wong.

Crowd: Presente.

ND: Francisco Gaspar-Andres.

Crowd: Presente.

RL: The Guardian recently published the names of the 31 people who died in ICE custody. Damico called out their names.

ND: Renee Nicole Good.

Crowd: Presente.

Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: The Workers Circle has a long history of social activism—125 years of everything from advocating for workers’ protection to marching in the civil rights movement to working to expand voting and women’s rights. Add to the list standing up for undocumented immigrants.

ND: We’ve been involved in all of those things. The continuity of everything we’ve been doing—it’s just in a new key right now. We’re people who believe in democracy, we’re people who believe in human rights, and we’re people that, most of all, believe in not sitting on our tails but we get out there and do. If there’s one way to characterize The Workers Circle, it’s as the people who have a national grassroots activist community that is on the frontlines working for our democracy right now.

RL: Michelle Jewell also spoke at the roadside rally.

MJ: It’s so wonderful to see so many positive faces and hearts in our community—in our presence today. What I told everyone is that, even though they can’t physically see our presence, they feel it. There’s been many times when the detainees have called to speak to their loved ones, and they find out that there are so many people here in support of them and fighting for their freedom.

“We are ALL immigrants.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: Michelle then introduced 16-year-old Booker High student Jodany Del Rosario. Her speech was met by loud applause from those assembled. She had a lot to say.

Jodani Del Rosario: I may not have been raised in religion, but I was raised with good morals and values. I was taught that, when something is wrong, you do not look away. You do not stay silent because speaking up is uncomfortable. You do not excuse cruelty because it has been legalized or normalized. You stand up. You speak out. You fight for what is right. And what is happening here is not right.

I’m standing here today as a US citizen. I’m standing here today as someone who is only 16 years old, who is a daughter of immigrants, who has family members who are undocumented and friends at school who came to this country seeking asylum. When I first started writing this speech, I honestly didn’t know what to say or how to say it. The weight of what this place represents felt too heavy for words. So I asked my mom for some help, and she told me to stop worrying about sounding perfect and to speak from my head and my heart. She told me to ask myself why I wanted to be here and why I chose to stand here today instead of doing 100 other things I could be doing on a Sunday evening.

“ICE out for Good.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

And the answer was simple: I refuse to accept that my country, a country that I was taught to love and respect, is turning into a circus—a circus in which human suffering is viewed as a spectacle. I’m here because I refuse to accept a system that cages people and then jokes about it. I’m here because I refuse to accept that cruelty is the price of safety.

Alligator Alcatraz is not just a name. It is a symbol—a symbol of how far we have allowed our humanity to erode. It is a place designed to intimidate, to dehumanize and to send a message that some lives are worth less than others—a place that relies on fear, isolation and a threat of nature itself to punish people whose only crime is existing without the right paperwork. There is something especially disturbing about the way this place has been discussed and defended—the jokes, the smirks, the casual cruelty of turning a detention center into a punchline. When we laugh at suffering, we lose something essential. When we normalize this, we teach ourselves—our children—that empathy is optional.

The people held here are not statistics. They are not invaders. They are not a problem to be solved. They are people who worked, who loved, who hoped, who prayed, who believed that this country might offer them safety. Many of them came here because they were desperate—because staying where they were meant violence, hunger, persecution or death. Seeking asylum is not a crime, wanting to survive is not a crime, and wanting a future is not a crime. Yet we have created places like this to punish them anyway.

Photo by Ramon Lopez

And here is the thing: I’m only 16 years old, and I cannot understand how the people who have lived—who have read history—who have seen what happens when systems like this exist—how they allow it to happen again. How is it that you know the system doesn’t work, and you let it repeat itself? In what world is treating human beings like this okay? In what worlds is leaving this world for the younger generation okay? I’m only 16, and I am watching the adults who were supposed to protect us fail, and it terrifies me.

As a 16-year-old, I’m also often told that I’m too young to understand politics—too young to have an opinion—too young to speak. But I know the difference between right and wrong; I know that no government policy justifies stripping people of their dignity; I know that no border is more important than a human life; I know that no border is more important than a human life; and I know that history does not look kindly on those who stayed silent while cruelty was carried out in their name.

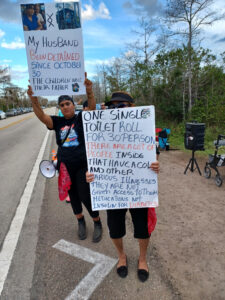

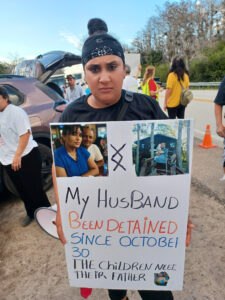

RL: As the event unfolded, a young woman with a megaphone stood on the side of the road, blasting the authorities within Alligator Alcatraz, who probably didn’t hear her pleas.

“They are not given access to their medications.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

Roxana Torres: [unintelligible] for his heart arrhythmia, and they don’t give you medicine! Shame on you! Immigrants come here for a better life!

RL: You see, her undocumented partner from Cuba with medical issues has been detained at Alligator Alcatraz since October, with his ultimate fate unknown. They have a one-year-old son.

RL: What is your name?

RT: Roxana Torres. I live in Fort Lauderdale.

RL: Is your husband undocumented?

RT: Yes. He reports every year to Miramar to renew his documents, but they took him in Miramar to move him in here.

RL: So he did report to immigration as required.

RT: Every year.

RL: But one day—what happened?

RT: October 30, they took him in Miramar. They moved him to here.

RL: In Miramar?

RT: Yes.

RL: And where was he when they took him? Was he at court?

RT: In Miramar. In the court.

RL: In court?

RT: Yes.

RL: So they were waiting outside and they took him, like many others.

RT: Yes.

RL: So he’s been here—so where is he detained? Is he right here? He’s here? He’s here in Alligator Alcatraz.

RT: Yes. In here. In Alligator Alcatraz. Yes.

RL: So what’s the situation here? Do you think you can—he’ll be able to get out, or what?

Roxana Torres. Photo by Ramon Lopez

RT: I trust in God, and I think [unintelligible], but he already has a lot of faith inside. He has a problem in the heart. He needs Plavix, Metoprolol for pressure, and they don’t give you medicine. In the same cell as he’s inside is COVID-19. And they don’t separate people for COVID. Everybody is together.

RL: So has he had any court hearings here?

RT: No.

RL: No immigration court?

RT: Nothing.

RL: Have you been able to speak with him?

RT: Yes. Every day, 15 minutes.

RL: So you are able to—he’s able to call out.

RT: Yes.

RL: You can’t call in, of course. So how is he doing? How is his—how is he feeling?

RT: He’s doing bad because he needs medication. The food is terrible. The water is contaminated. If you complain about the food, ask for medicine, they put the person in a private cell. Very cold temperature and no clothes, and only one food per day if they complain for something.

RL: Only one what per day?

RT: Food. One food per day.

RL: Oh, one meal?

RT: Yes.

RL: One meal per day? Is that all?

RT: Yes. When you complain for something.

“Stop cruelty.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: He is originally from what country?

RT: Cuba.

RL: He’s Cuban?

RT: Yes. Like me.

RL: Like you. You’re Cuban? So how long have you all been in the United States?

RT: Like 20-something years.

RL: 20-something years. So he’s been here a long time. What was his work before?

RT: Landscaping. Monday to Sunday, and paid taxes every year.

RL: How did he arrive in the United States?

RT: I don’t remember the name in English.

RL: But he came in by a boat or crossed through Mexico or what?

RT: No. He came in on a plane.

RL: He came in on a plane? But he probably came as a visitor but he just didn’t start the process to become a citizen. So his visa had expired, basically. And this is 20 years ago?

RT: Yes. 20 years ago.

RL: And you’ve been here 20 years?

RT: No. Me? From 2014.

“ICE melts under resistance.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: So you met him here?

RT: No.

RL: You knew him from Cuba, then?

RT: No. Not married yet. I tried to marry him, but he doesn’t have any documents.

RL: Okay. But he’s your husband, but you’re not officially married.

RT: Yes.

RL: And your child—?

RT: My child is inside the car.

RL: What’s his or her name?

RT: Diago.

RL: And how old is Diago?

RT: 12 months.

Photo by Ramon Lopez

RL: Now, is your husband—?

RT: Father.

RL: The father is your husband.

RT: Yes.

RL: Is he thinking about self-deporting?

RT: I trust in God, and I think [unintelligible].

RL: You trust in God, and you…?

RT: I trust in God, and I think [unintelligible.] He won’t deport.

RL: He’s not going to deport?

RT: Yes.

RL: Okay. So he’s going to fight this and hopefully stay in the United States.

RL: The December report from Amnesty International alleges inhumane treatment and torture of detainees at Alligator Alcatraz as well as unsanitary conditions there.

Not attending the protest was Dianeth Dorris. She’s Michelle Jewell’s mom and lives with their daughter in Venice. She emigrated to the United States when 27 after suffering hard times in Colombia.

Dianeth Doris. Photo by Ramon Lopez

Dianeth Doris: I had some kind of sickness—a viral sickness—and I was paralyzed for years. Completely paralyzed. I couldn’t talk; I couldn’t move my hands; I couldn’t do anything. I was practically a vegetable. But my parents took good care of me and found the right doctor—because they took me to a lot of doctors. None of them were able to do that disease—and it took me until around 12 or so that I was able to start moving. And my parents really, really took good care of me. They took me to every place that they said there is a good doctor. They took me there.

RL: Dianeth happily became a U.S. citizen but no longer feels safe in America because of her brown skin and Spanish accent.

DD: And I start getting nervous that I can’t even go out for a walk. I can’t go do this. I can’t do that. I can’t do that. And now I’m getting like a prisoner. I feel like I am a prisoner.

I am American citizen on paper. I can’t say that I am not treated because I have not been mistreated, but with these new regulations and everything like that, I am really scared to—again, I’m saying—just to go up for a walk in the streets. I can be on the street taking a walk, and they can grab me, and who’s going to say, “don’t do that”?

Here? I’m sacrificing my life. Being grabbed and taken to a place that doesn’t have any beds or drinking water or nice food to eat. That’s what I’m sacrificing being here.

RL: So, after much thought, Dianeth has decided to go elsewhere. She said it isn’t safe to return to Colombia, so she’s moving to Costa Rica. This WSLR reporter met with the 84-year-old who lived and worked in the metro Washington DC area before moving to Florida two-plus years ago to stay close to her family. She has a one-way airline ticket to Costa Rica, where she has neither close friends nor family, but she believes she must leave the country she had loved and adopted but now feels doesn’t want her.

Will she ever return to America? Maybe, but not while the White House’s current hard line immigration policy remains in effect.

RL: So, final question. You ever going to come back?

DD: It depends. If this thing that’s going on disappears, yes. But I doubt it. But I don’t know. I never know. If everything disappears and we are not being treated like criminals because we have a different color of skin, why not? I enjoy life in Washington DC, in Maryland—in the United States.

RL: Do you feel sad about leaving the United States after all these years—even though you’re going to a nice place, I’ve been told—but do you have any degree of sadness about leaving?

Michelle Jewell with her mother, Dianeth Doris. Photo by Ramon Lopez

DD: No. The only—not even my daughter and the kids, because I know they are in contact with me. We can talk every day; we can tell stories about every day. We do that, basically, living here and when I was living in Colombia, so I don’t think I am really separated from them.

RL: Will you miss living in America?

DD: I don’t understand about the political situation.

RL: But will you just miss living in America regardless of the politics?

DD: I guess so, but I have never been into politics, so I don’t know anything about it except if they treat you decent or mistreat you. Period.

RL: Her family. Michelle, her husband Albert and granddaughters Maya and Alexandra support Dianeth’s that move. They will dearly miss seeing her each day but feel there’s no other option available. So says Michelle.

RL: What do you think about all this?

MJ: I think my mother is an unbelievably positive person. No matter what question you ask her, she’s going to be like, “Yeah, I’ll be fine” because she’s a go-getter. Obviously, she’s the pioneer of my family. She’s the one who came here and she said, “I’m going to make it no matter what.” But, of course, this has been her home for—she chose this as her home—since 1969. One thing is to choose to go back to Colombia or go to Costa Rica because you want to. The other thing is because you’re truly fearful. That is definitely why she’s leaving, and the straw that broke the camel’s back, if you will, is that, until last year, statistically, what we had read was that the administration would de-naturalize an average of 11 citizens a year, and this year, the goal is 100 to 200 per month starting this month. So they may say that they’re going after criminals, but that’s also what they said when it came to who they’re detaining now, and we’re already seeing that they’re detaining citizens. They may say, “Oh, well, that was because they were infringing” or “They were interfering” or whatever it is, but what we continue to hear and see over and over is that they’re just becoming more and more aggressive for the pleasure of doing so. And that is scary.

RL: So Dianeth boards a jetliner for Costa Rica next week to face the unknown, and Roxana will continue to drive from Fort Lauderdale to Alligator Alcatraz on Sundays to angrily and noisily protest her partner’s detention with no freedom in sight for the Cuban immigrant. But what is clear is that the Alligator Alcatraz prayer vigils, which have been conducted since August, will continue. So says Noelle Damico.

Photo by Ramon Lopez

ND: We come together to say no to ICE. We come together to say no to the gulag archipelago of the detention system in this country. We come to say no to the torture that is going on inside Alligator Alcatraz and in other centers that has been documented by Amnesty International. And we say no to Governor DeSantis as he brags about abducting 20,000 people this year. Shame! Shame! As he eagerly discusses the expansion of this model of detention system elsewhere in this state. We say shame. We say no. And when it comes to Alligator Alcatraz, what are we going to do?

Crowd: Shut it down!

ND: What are we going to do?

Crowd: Shut it down!

ND: I can’t hear you.

Crowd: Shut it down!

“No human is illegal.” Photo by Ramon Lopez

ND: Friends, when you leave this place, I want you to tell five people that don’t know about what’s going on here about what you experienced. We are here week after week. This is our 24th consecutive week outside of Alligator Alcatraz. 24 weeks. And we have the commitment to go the distance. So let’s just say 24 out of 52 unless we can get it shut down sooner. But we’re here to go the distance, and we’re here undivided. We are here united.

RL: This has been Ramon Lopez with a WSLR News special report.

WSLR News aims to keep the local community informed with our 1/2 hour local news show, quarterly newspaper and social media feeds. The local news broadcast airs on Wednesdays and Fridays at 6pm.